To sleep or not to sleep: the ecology of sleep in artificial organisms

Abstract

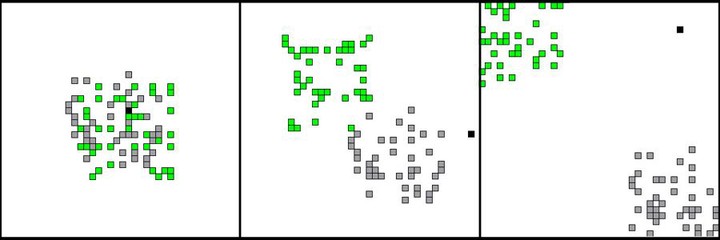

All animals thus far studied sleep, but little is known about the ecological factors that generate differences in sleep characteristics across species, such as total sleep duration or division of sleep into multiple bouts across the 24-hour period (i.e., monophasic or polyphasic sleep activity). Here we address these questions using an evolutionary agent-based model. The model is spatially explicit, with food and sleep sites distributed in two clusters on the landscape. Agents acquire food and sleep energy based on an internal circadian clock coded by 24 traits (one for each hour of the day) that correspond to “genes” that evolve by means of a genetic algorithm. These traits can assume three different values that specify the agents’ behavior: sleep (or search for a sleep site), eat (or search for a food site), or flexibly decide action based on relative levels of sleep energy and food energy. Individuals with higher fitness scores leave more offspring in the next generation of the simulation, and the model can therefore be used to identify evolutionarily adaptive circadian clock parameters under different ecological conditions. We systematically varied input parameters related to the number of food and sleep sites, the degree to which food and sleep sites overlap, and the rate at which food patches were depleted. Our results reveal that: (1) the increased costs of traveling between more spatially separated food and sleep clusters select for monophasic sleep, (2) more rapid food patch depletion reduces sleep times, and (3) agents spend more time attempting to acquire the “rarer” resource, that is, the average time spent sleeping is positively correlated with the number of food patches and negatively correlated with the number of sleep patches. “Flexible” genes, in general, do not appear to be advantageous, though their arrangements in the agents’ genome show characteristic patterns that suggest that selection acts on their distribution. Collectively, the output suggests that ecological factors can have striking effects on sleep patterns. Moreover, our results demonstrate that a simple model can produce clear and sensible patterns, thus allowing it to be used to investigate a wide range of questions concerning the ecology of sleep. Quantitative data presently are unavailable to test the model predictions directly, but patterns are consistent with comparative evidence from different species, and the model can be used to target ecological factors to investigate in future research.